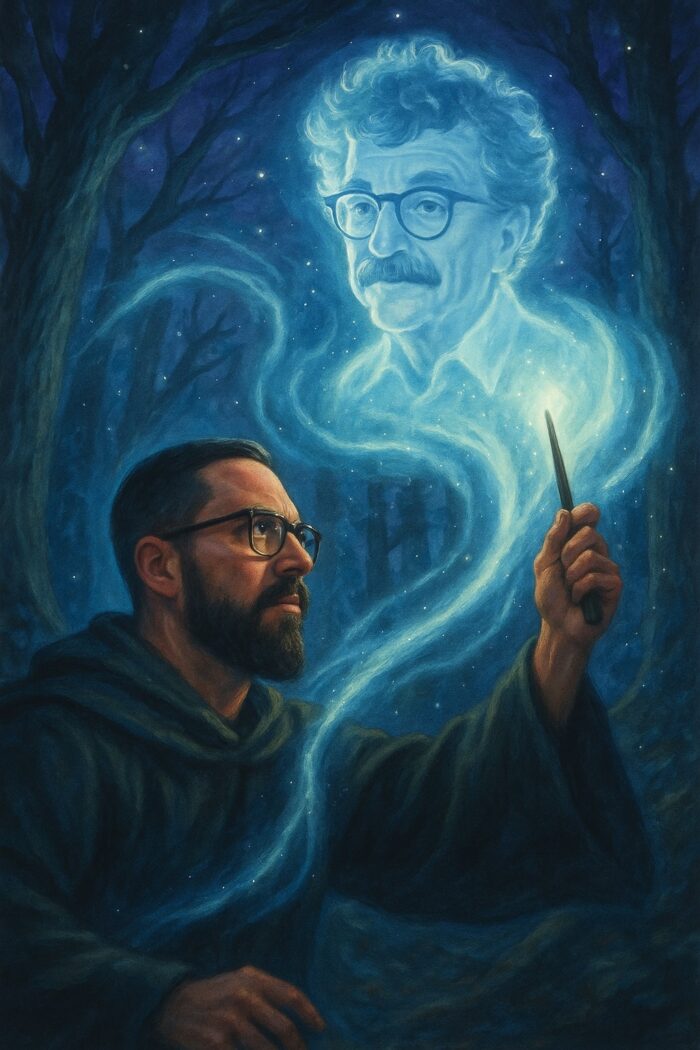

Last year was difficult for a litany of reasons. It wasn’t the students. Nor was it the teaching itself. For English teachers (if not all teachers in general), there has been a very serious societal shift that has been oncoming for years, if not decades. But what you are reading right now will not be about said shift. This is an essay, not a volume of books. But the amazing news, for me anyway, was that Kurt Vonnegut came to my rescue last year. He single-handedly dug me out of negative self-talk and dragged me most of the way up some metaphorical mountain where he resided, on its peak, in a ghostly form, expounding bits and pieces of wisdom that have since re-jiggered my perspective to that of someone who is content and need not climb anymore mountains, at least for wisdom. I’m okay with still climbing mountains for the sake of fitness, adventure, and getting rid of evil rings.

This phenomenon of a personal upheaval assuaged by an author who has been gone for almost 18 years, it’s just amazing that someone’s post-life popularity and existence in the things I was engaging in helped me in a very visceral sense. So much so that by the end of my year of exhaustion, I used the tool I was mostly exhausted from to create something that was funny and delightful and meaningful to me. Let’s get that to you right now:

This Vonnegut phase of mine started two years ago when a colleague mentioned that I should read Vonnegut’s first novel, published in 1952: Player Piano. If you don’t know, a “player piano” is a computer–it reads hole-punched music sheets on a mechanical scroll and “presses” the corresponding keys. Essentially, a computer digesting an algorithm. The output: music.

Vonnegut had worked at General Electric as a PR guy, and this book was wrought from that experience. You may now be thinking of Ray Bradbury if you are also a fellow English teacher. He was interested in the same sorts of things, our relationship with technology, though it was entertainment that was the main focus of his 1953 novel, Fahrenheit 451, a novel I have taught every year for a while now. I had no idea Vonnegut and Bradbury dealt with the same sort of themes in their work. In retrospect, it makes sense. One analyzed our dalliances with tech with fantastical and serious futurism, the other with satire.

Player Piano is not Vonnegut’s best work, but it’s better than most. And it’s one of those books that constantly makes you check yourself in terms of your own history.

It’s very human to think that we ourselves are the first ones to encounter a problem. This brand of temporal solipsism–that we believe our problems are modern and endemic to our age, in this case our technological prowess, and never before encountered–_Player Piano_ smashes to bits. The technological problem Vonnegut tangles with in Player Piano is our fascination with efficiency. And we don’t have to go deep into history to find other previous examples, for instance Karl Marx and the Luddites. But Vonnegut’s examination of 1950s work-life is highly prescient and very relevant.

Immediately upon finishing Player Piano, I read A Man Without a Country, the last book he published while alive. Fitting that. To finish Vonnegut’s most idealistic work of fiction, a first attempt, one not so artistic in shape and scope–not like his later works–and find Vonnegut tottering around in the early 2000s, reignited in the nonfiction essay realm. But I had also read his first book and his last, as if I myself was time-traveling around Vonnegut’s intellectual life through a literary wormhole.

I wrote this about A Man Without a Country in Goodreads:

Do not be fooled. Despite its age and analysis of the “present” in early 2000, this book is still relevant.

A wee bit too cynical, but there is a lot of truth. Read it for the way Vonnegut winds his way through a point he wants to make, getting there with three seemingly unrelated metaphors. Masterful.

During _A Man Without a Country_–the two days it took me to read it–I was googling videos of Vonnegut’s last book tour. I remember watching one of these interviews with Jon Stewart back when I was in college, wondering, whoa, that guy smokes like crazy and is still alive? Re-watching this interview sparked a memory of some sort of Kurt Vonnegut documentary that had come out a couple years ago but was yet in theaters out of my range to attend. Now, two years later, it was available: Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time. It was created by Robert B. Weide, famous for being a director and producer for Curb Your Enthusiasm. The documentary is surprisingly touching and eminently recommendable.

I surmise that many acerbic minds like Vonnegut’s are easily dehumanizable. It is sometimes hard for us to glue the creative wit to an actual human who, like us, eats leftovers or finds brushing their teeth a boring but necessary affair. And I suspect that documentaries of writers, at least those who are only in the public sphere through their words, really do a lot for filling in the gaps for us readers.

Then again, these two paragraphs I read recently, written by Noah Hawly in The Atlantic, do a pretty good job of humanizing Vonnegut:

The Army taught him to fire howitzers, then sent him to Europe as a scout. Before he left, Vonnegut surprised his mother, Edith, by going home for Mother’s Day 1944. In return, Edith surprised Vonnegut by killing herself. That Saturday night, she took sleeping pills while he lay unaware in another room.

Seven months later, Private First Class Vonnegut was crossing the beach at Le Havre with the 423rd Infantry Regiment of the 106th Infantry Division.

Before I read this article, that same colleague who told me I should read Player Piano took her family on a sidebar trip to the Kurt Vonnegut Museum & Library in Indianapolis. And then she began reading Pity the Reader: On Writing With Style by Suzanne McConnell, one of Vonnegut’s students and life-long friends. I followed suit. It is an amazing book.

I can find thousands of articles on the benefits of reading–and often find myself doing so–but none of them hold much to the motivating factors of a Vonnegut snippet. Such as this one:

Don’t give up on books. They feel so good–their friendly heft. The sweet reluctance of their pages when you turn them with your sensitive fingertips. A large part of our brains is devoted to deciding what our hands are touching is good or bad for us. Any brain worth a nickel knows books are good for us. (McConnell 152)

Or, really, just about anything: “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be” (McConnell 341).

Months after finishing the book, I read an amusing article about AI company logos and found this reference:

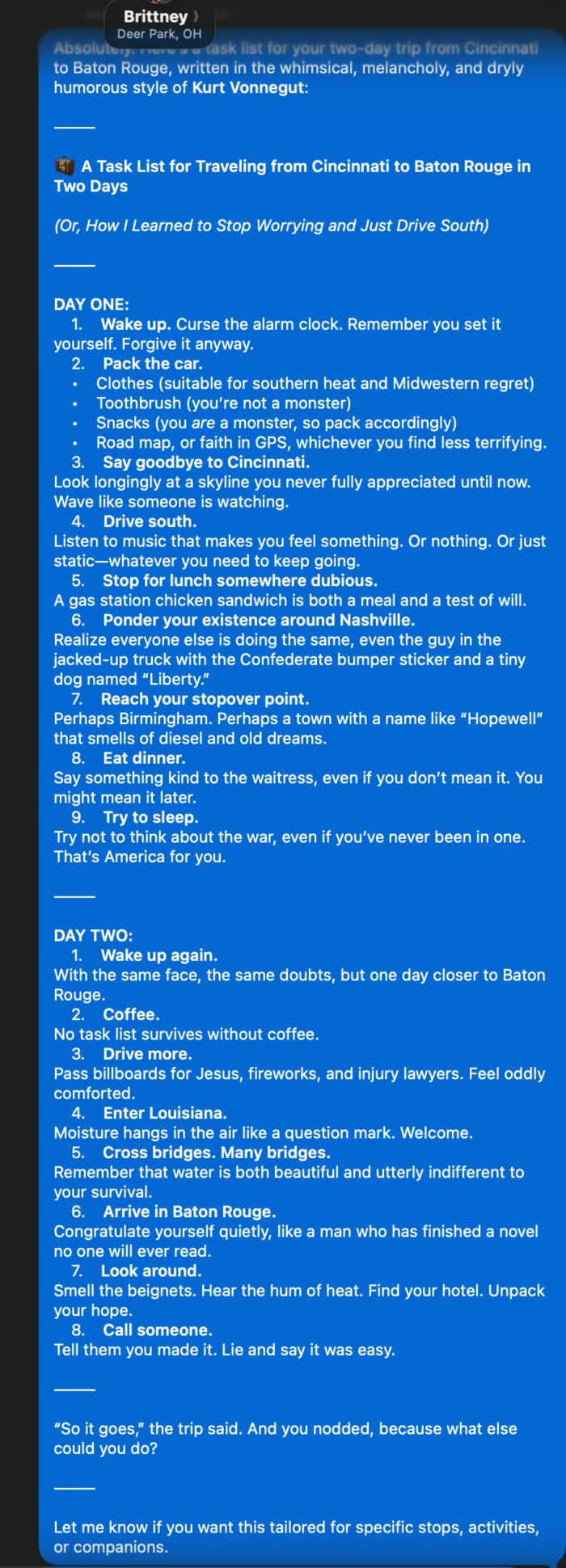

This summer was to be our first time road-tripping with a child, a one-year-old. Someone told me that I should plot out my trip in ChatGPT. See if I could get any insights. I did so. It was boring. So I asked it to give me travel directions as Kurt Vonnegut. I sent the results to my wife:

Though it may have its problems upon many different standards of ethics and veracity and parody and such and so forth, it was pretty good. It gave me a couple chuckles and a sense of wonder. At that time, it was the best thing that ChatGPT had ever made for me. (Though I should say that nothing ChatGPT has ever made for me has been necessary or that important. But, funny, yes.)

Later, on a different trip to Baton Rouge, we went down to New Orleans. I wanted to visit Faulkner House Books, which is the smallest bookstore I have ever shopped at–a tiny room full of amazingly curated books. It was beyond charming, and one of the books I picked up was TheBookshop by Evan Friss. It’s about America’s bookstores throughout the country’s short lifespan. Len Riggio, longtime executive chairman of Barnes & Nobles, connected me again to another Vonnegut allusion:

Short and approaching eighty but still powerful looking, Riggio was in jeans, sneakers, and a striped sweater. He walked with purpose over to the scratchboard portrait of Kurt Vonnegut, a style any Barnes & Noble regular would recognize. “I was very close to him,” Riggio said. (Friss 227)

After our first Baton Rouge trip, we got ready for the next summer excursion–a trip to Cape Cod. Having learned that Vonnegut lived in Cape Cod himself, I thought it fitting to bring my next Vonnegut book: The Breakfast of Champions.

I bought my copy a long time ago, back when I lived in Nashville and frequented one of the best used bookstores in America: McKay’s. I would go there almost every weekend, meticulously perusing the shelves of each section of my interest, which would end up being most of the sections in the store. Early in my relationship with McKay’s, I remember finding books from such famous but niche authors like Haruki Murakami or Paul Auster or Italo Calvino for $1-$2. It was insane to me and made me religious in my perusals of what deal I could find next.

Picking up my copy of Breakfast of Champions, purchased at McKay’s, now 10 years away from having lived in Nashville, it was doubly nice to inhabit an artifact itself published in 1973 that certainly took me back in time as well as forward.

Breakfast of Champions is certainly a book that a veteran author could write. Where Player Piano is irreverent but didactic, Breakfast of Champions is irreverent to be didactic.

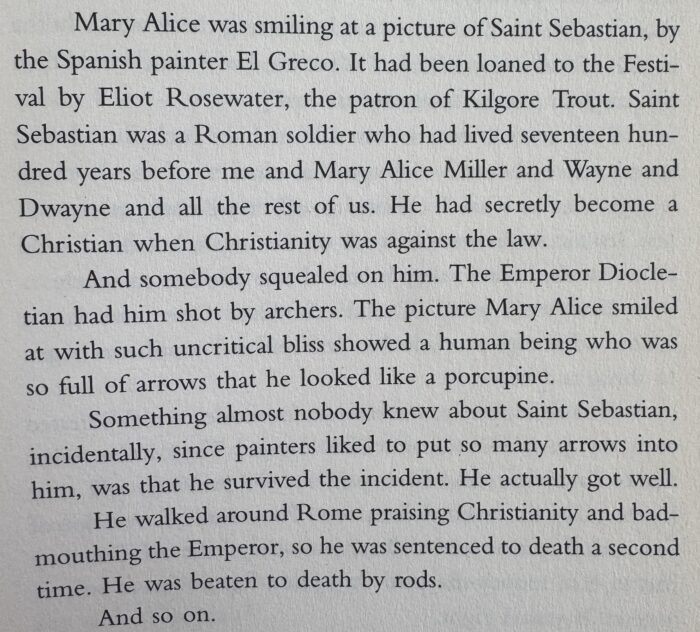

And then, amidst its pages, I was returned to a memory of my youth that was now to be corrected.

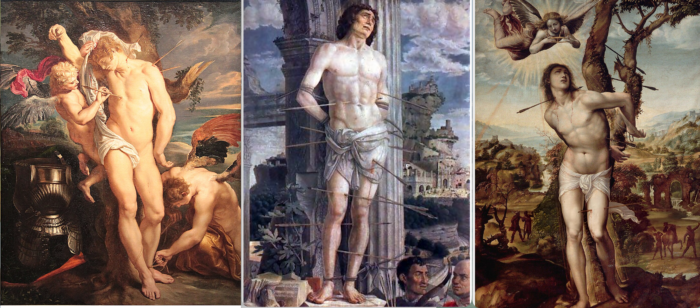

When my family lived in England, we took copious trips and vacations to any place within our scope of travel. We needed to get our fill while it was affordable and close in proximity. One of the places that was certainly necessary to visit was Paris. In the Louvre, my sister made family history by finding paintings of martyrs being killed and asking a simple question, “Is he dead?”

This kept on for several paintings. The pinnacle of her question-asking came when we came across a painting of a dude with a quiver of arrows protruding from all parts of his body. We laughed. The guy was peppered with arrows from close range. He was most assuredly a goner. At least that’s what my memory tells me. We told this charming story–my sister the worried and quizzical evaluator of unfortunates painted and hung up for all the world to see–over and over, year after year.

One time, not long after smartphones first found their way into our pockets, we found ourselves laughing once again at my sister’s innocent remarks. Curious, I took my smartphone out and tried to find the painting my sister had asked about. It was hard to google, so I gave up.

But here, in Breakfast of Champions, I found my answer. It was Saint Sebastian:

There are multiple depictions of Saint Sebastian in the Louvre. None of them look familiar to my memories at all. And I didn’t realize that there was also a statue amongst the depictions. And I really, really didn’t realize that there was a depiction of his recovery.

Yeah. He survived. I found this out while group texting with my family about my findings. You only need to go to the third sentence in his Wikipedia page to see that he survived the ordeal.

We were wrong to scoff at my sister’s question. That arrow mottled dude wasn’t dead. He recovered. Though, not long afterward, he was “clubbed to death.” Sheesh.

This was not to be the only long held belief I would renegotiate in lieu of Vonnegut’s continued presence.

I have the habit of helping my library store its copious amounts of books. Meaning, I checkout a lot of books and keep them in my house for later, if that ever happens. I read some of them and return the rest when their automatic checkouts run out.

One of the more recent curiosities I’ve checked out is a book mentioned by someone I follow (I think it was Audrey Watters): Education and the Cult of Efficiency by Raymond E. Callahan. I took pictures of the opening and closing lines of the book and sent them to several group chats of colleagues and other teacher friends and asked them what year they thought the book was written. I think the typeface and the yellowed pages probably gave unintended hints, but, here, I’ll copy them in digital text form for you to guess:

Here are the opening lines:

When I began this study some five years ago, my intent was to explore the origin and development of the adoption of business values and practices in educational administration. My investigation revealed that this adoption had started about 1900 and had reached the point, by 1930, that, among other things, school administrators perceived themselves as business managers, or, as they would say, “school executives” rather than as scholars and educational philosophers. The question which now became significant was why had school administrators adopted business values and practices and assumed the posture of the business executive? Education is not a business. The school is not a factory. Of course, by 1910 the scale of operations in both business and education (in the large cities) had produced large organizations, and so it was reasonable and even legitimate to expect the borrowing of ideas and techniques from one set of institutions to another. But the evidence indicated that the extent of the borrowing had been too great for such an explanation to be adequate.

One paragraph in and Callahan has yet to mention that one word that makes the title of the book, something our curiosity has been hellbent on finding before our species of humans began messing with things–our one-word motto: efficiency. But you can see it’s going there.

Here are the last lines (I feel like I’m committing a major offense by doing so, but I think this book is worth semi-spoiling):

It is true some kinds of teaching and learning can be carried out in large lecture classes or through television but other vital aspects of the education of free men cannot. Until every child has part of his work in small classes or seminars with fine teachers who have a reasonable teaching load, we will not really have given the American high school, or democracy for that matter, a fair trial. To do this, America will need to break with its traditional practice, strengthened so much in the age of efficiency, of asking how our schools can be operated most economically and begin asking instead what steps need to be taken to provide an excellent education for our children. We must face the fact that there is no cheap, easy way to educate a human being and that a free society cannot endure without educated men.

So, the focus on a certain gender is definitely a clue that it wasn’t written in our most recent years, but, dude, whoa: Can you feel that? Yes, this paragraph is a ghost, haunting all education conversations even now. And for the reveal: This was written 63 years ago. I wish I had read it in college. I would’ve had a far better scope of what my role as an educator was to be if I did.

So I was following Vonnegut and Vonnegut was following me. The whole experience was like when you buy a car and see that your brand of car is now everywhere. And coincidentally, Vonnegut used to sell cars. Saabs, if you want to know. On Cape Cod.

Someone like Vonnegut will always peek out from time to time in our worlds. Even now, I’m listening to a podcast about another popular and philosophical science fiction writer who counted Kurt Vonnegut as a major inspiration. As I was listening to Arvind Ethan David’s Douglas Adams: The Ends of the Earth, I could almost sense it coming as the wind-up was occurring.

But the truth of all of this is that I have never really been without Vonnegut. As an English teacher, I have taught Harrison Bergeron a ton of times and for the last several years have taught John Green’s essay “Indianapolis” from The Anthropocene Reviewed, which has a healthy dose of Vonnegut in it for obvious reasons.

It’s just that each time I encounter something new of the man, I’m further wowed. I know that will end, of course. There is only so much we leave on this earth and so much less while dead. I’m no super stan, but I know that when he and I encounter each other again, although it will be severely one-sided, I will be thankful that he thought his thoughts and put them out for me to find, so much later, in the sidebars of another life.