The Answer to the Title by Both Me, the Human Author, and ChatGPT

First of all: No. It won’t.

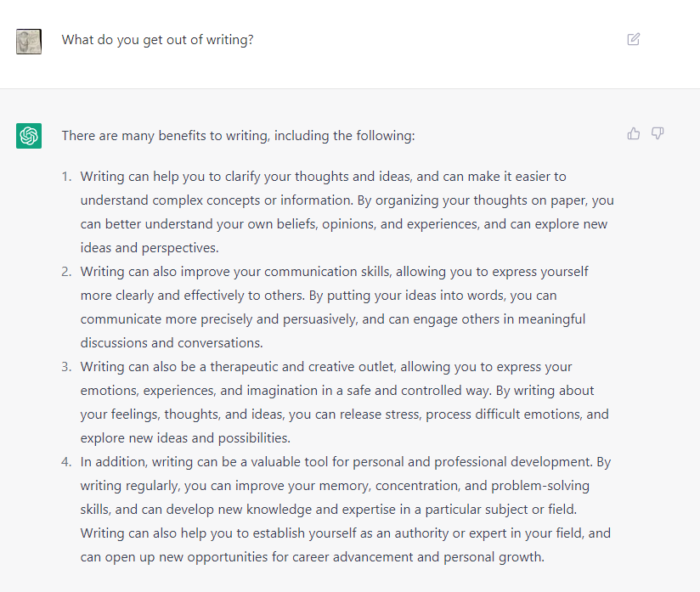

It even admitted as much to me:

The Trickery of Reading What You Thought Was a Student But Is Actually a Robot

Is ChatGPT’s answer a definitive one? Probably not. But it’s a good one. One you’d think was written by a human 20 years ago.

But let’s get to it: Will students use ChatGPT or other AI to cheat?

Sure. Of course.

As a teacher, finding evidence of plagiarism is a horrible experience. Your first thought is always, “Man, this really shows how much they respect what I’m trying to do here.” And then the disappointment runs from there. All the while, you are worrying what kind of strain this puts on an academic relationship.

In my career, I’ve caught students copying and pasting work from other students or just straight from the internet. Others have tried to recycle essays from their friends in other classes or from students from previous years. With digital documents, it’s not too difficult to do.

At my previous school, we had access to Turnitin.com, a plagiarism detecting suite. You’d think telling students that you are running their work through Turnitin.com would eliminate all plagiaristic efforts. Nope. It still occurred. I’ve even had arguments on what percentage of “originality” constitutes cheating.

For the last 8 years, I’ve been without it. The school I currently work does not have a Turnitin.com license. And, you know, It’s been just fine. (Honestly though, with Google Docs’s Revision History and searchable text, it’s difficult to get away with it if you are suspected.)

Writing that small snippet about Turnitin.com made me curious to see what has happened with Turnitin.com, and so I decided to visit the website. At the top of their homepage is this heading: “Empower students to do their best, original work.”

Interesting. Are students only able to do their best work because their work will be put through a security plagiarism check? How did we get to a place of paranoia where cheating has gotten so rampant that we lament the state of education?

In 2008, Barry Gilmore published Plagiarism, a book about students resorting to cheating, mostly in writing.

I think what Gilmore does rather well is to outline why anyone would want to plagiarize. He says, “For many of us–and I include myself–it’s easy to view plagiarism as an indicator of overall academic achievement: good students write, poor students plagiarize.”

Gilmore lists the following reasons students resort to plagiarism:

- student confusion;

- external pressures;

- cultural expectations; or

- perceptions of ease.

The first two are the most interesting. They stem from making sure an assignment is written the right way. It’s because students want a good grade or at the very last want to be perceived as competent.

I think the most interesting argument that Gilmore makes about plagiarism concerns assignments themselves.

If a teacher reuses an assignment, with our digital tools, it’s easy to copy it for another’s use, especially when a lot of teachers in a school use the same assignment. And if a student determined that the assignment was too confusing, or there was too much riding on getting it right, or the school’s student cultures didn’t hold value in doing the assignment (this is the one I would have latched onto as a high schooler: it’s been done before, therefore it has lost it’s value to be done again), or it seemed easy to get away with, then a student might copy and paste that assignment and do all sorts of things to make it look like their own work, including doing nothing.

But if a teacher helps students design their own prompt, then that at least takes out three of the four reasons students plagiarize. The remaining reason to plagiarize, external pressures, are tied most specifically to grades, and that is a related but separate issue that a thing like ChatGPT should make us reevaluate.

Gilmore’s book was situated in the land of 2008. Plagiarism is nothing new. Paper mills and just plain old copying and pasting from the internet have been around for longer than 14 years. I remember when I was in 6th grade and had no idea what plagiarism was, I got away with copying part of an excerpt from a book I got from the library and putting it in an essay. Granted, I had only a vague idea that this was wrong.

So, as AI becomes a plagiarism tool, what now? Will some company, like Turnitin.com, come up with AI sniffing algorithms to defend the virtue of a student’s autonomous writing?

Man. I have no idea how that would work.

Is it needed? I know you could still use the old Google Doc “revision history” check for copying and pasting, either from an essay available online or an AI’s uniquely generated writing. But that’s a lot of work. Fortunately, us English teachers can still rely on the tried and true: English teachers develop a sense of what a student is capable of when we get to know that student and read their work.

The only reason a teacher might not be able to discern plagiarism is if the amount of students we are tasked with teaching is too much. Even then, a simple conversation about their writing reveals a lot.

But it’s Gilmore’s last reason (“perceptions of ease”) that has the internet abuzz.

Humans Have the Innate Need to Create and Tinker

Will we engender laziness with our own technology?

Yes. We already have. My recliner is pretty great. Not having to catch my own food every day is also pretty great. To worry about technology increasing human laziness isn’t that ridiculous of a worry. Tools are supposed to make things, at least, easier.

But we forget that the human species is inherently curious as well as natural modifiers of the things around us–if not creators (which one can argue is modifying one’s environment to produce something new). Our histories are lined with tools, both good and bad, and the tinkering that occurs with them. I mean, look around you. Isn’t it amazing that we have invented robots that have helped make most of the stuff that we come in contact with?

But I get it. People unfairly getting away with achieving perceived skills, let alone students, is not something we want.

My favorite bit of argument against worrying about AI so far comes from Ian Bogost’s take in The Atlantic. Bogost points out that relying on AI to write would just be, like, really boring, both in terms of output–AI are yet not the greatest stylists–and in terms of what one has really done with their time.

If passive things like scrolling social media show we are depressed, or passive things like scrolling social media make us depressed, what would passively going through high school be like?

In plainer words: If we are worried that our children won’t struggle to improve the skills with something as important as writing, then what kind of education have we created?

If our eye is on product, then we have missed what education is about.

And, sort of, we have.

The big two philosophical arguments bandied about education when I was in grade school was whether or not cursive was still relevant given the increasingly computerized culture and whether or not students should be denied the use of a calculator until the underlying skills the calculator supplanted were understood.

In my youth, I was annoyed by both arguments. Mostly, I thought, who cares? Technology always gets better, and it would be ridiculous if we didn’t take advantage of new and current technology and just get on with it. Let us learn to type and forget cursive. Or let us use calculators and progress onto other math things.

Many years have passed since my grade-school indignation. Now, I think of all this differently.

Some would say I’m the opposite of a math teacher–I’m an English teacher–so I’m not sure what the real expertise is about learning and the use of calculators, but I know that those who want students to do without the calculator want their students to practice a type of focus. The absence of a calculator necessarily means slowing down. It is the same with writing longhand instead of typing. And that’s not so bad.

This is a confusion of importance. Is it the product or the process?

For my entire career, education has been about product, for schools, teachers, and students. Schools must have good graduation rates, which doesn’t seem like the best indication of quality. Teachers must show they are good teachers through standardized tests. Students must show they are qualified to go to college through standardized tests, a 600 word essay, and a transcript.

We are sacrificing quality for quantity. This makes sense. When you have limited resources to improve a huge population of students, you tend to want to make things more efficient. So you work in “best ofs.” With our system, these are the best indicators we got. Or at least, we think it’s the best we got.

ChatGPT is an extension of this. Here is a thing that can provide passable written answers. But the answers themselves are yet not true. The questions will largely dictate the answer, and the algorithm will dictate the knowledge it provides from its database. What of this is advancing the conversation of ideas? It is akin to the linking of an internet article from some source. How do we value one over another? How will AI understand the vast arrays of peer reviewed data? We know not. We worry that our students will use it as a product of their work.

So, if ChatGPT can create great informative essays–like college essays, job applications, literary essays about long discussed books, and knowledge questions you’d see on tests–then perhaps we are not really living in the realm of education we thought we were.

Once Again: Humans Are Humans

Sometimes it astounds me that reading is not a natural human ability. It’s a skill adapted from various parts of the brain. Reading serves as a reminder of our brain’s astounding plasticity. But though machines can be said to read too, we do not read like machines.

I just listened to an interview of Maryanne Wolfe (from reading and human brains fame) on The Ezra Klein show where Wolfe and Klein discuss Wolfe’s idea of a “biliterate brain.” It made me re-confront the type of reading Klein, Wolfe, you, and I do on a daily basis. We mostly read or skim digital text. And then, we read mostly on paper for things we want to slow down for.

Our world consists of both digital and analog reading. It is inescapable. Weirdly, that seemingly unimportant difference in medium is something we need to be mindful of. It’s an interesting branch of research and a reminder of how small things can be of most importance to how humans function.

The best reminder of how humans totally underestimate our own flesh, blood, and brains came when Klein and Wolfe’s conversation led to the idea of reading a book versus reading the summary or the “facts” of a book. A book distilled. I have seen a lot of techies pronounce this as fact: You don’t need to read an entire book. That’s a waste of time. Too much filler. Efficiency!

Wolfe’s rebuttal is that books afford “contemplation.” We are temporal beings, and though we’d love to rush things, humans need time to sit with things in order to understand them better.

Furthermore, we crave story not a series of bullet-pointed facts. It’s why we are so engrossed by gossip. We love drama; we love conflict. It is our chosen method for relating anything. Even people with business plans looking for an investor need a story for their pitch, which is why we had a ton of those “save the world” tech ideas in the early internet age.

Contemplate this: Our lives are way more safe and comfortable than our savannah days in Africa. and yet we create oodles of stress.

Our biologies have not improved with our tools or our civilizations. In the grand scheme of our lives, we shouldn’t be stressed that we have potentially offended a stranger by bumping into them to get onto the subway. Our bodies don’t understand that we live in a land of plenty, of Whole Foods and McDonald’s. When we try overcorrect the abundance we have put into our bodies, our bodies rebel by activating our natural proclivities to not starve to death or be susceptible to a weakness. An efficient system has fail-safes, and when we lack food, our brains give us added biological motivation.

Let’s look at a major educational tech-topian idea we’ve grappled with recently: online learning. We thought that this might replace schools. It would be far cheaper and more convenient. The pandemic brought that into starkness. We realized that online teaching is only wonderful to have if the alternative is nothing.

With all our awesome understandings of our own biology and all our awesome tools, how could we not foresee the power of humans simply being in the same room.

Efficiency for efficiency’s sake breeds a life humans really don’t want to live in, even though we are all striving for it. It’s a tale we learn again and again, much like hubris–which you can argue this is a type of hubris: us thinking we can be as efficient as a machine.

But, as we have learned from a decade of hot takes, clickbait, social media posts, and internet headlines, it is most assuredly always better for our minds to take things slowly in order to empathetically shovel data into our brains.

I am sure there is a use for ChatGPT, but I’m not sure that anyone would like to intentionally read something a robot wrote.

And like ChatGPT said (if AI can “say” something or have a position) at the beginning of this essay, there is still a need for writing. And there is still a need for reading other humans’ writing.

Perhaps it will one day fake it all with aplomb. The AI can only get better, but if your idea of writing and reading is to grub up information and to make efficient our writing and reading of it, it won’t be a satisfying one, almost categorically.

I’m not saying that this sort of functionality isn’t helpful. In that Ezra Klein Show interview, Wolfe mentions that digital reading is a lot of skimming and finding. Reading isn’t one thing. Nor is writing.

Where writing is a really great tool is when we are trying to organize our own thoughts or to relate to other humans with story. It is the writing itself that causes better thinking. Writing is organized thought.

We may be able to escape a lot of things in our species’s run, but we can’t escape being human.

You Speak of Idealism, Sir

I don’t think you get into education without being driven by some sort of idealism. Actually, I don’t think you get into anything genuine without some sort of idealism.

Yes, in curriculums across the land, ChatGPT cheating could thrive. But would it really? Would it, as this headline states, be “The End of High School English”?

Students aren’t naturally nefarious animals. They are humans too. Most of them mean well and are altruistic. They do not want to insult or let down their teachers. They also do not want to fall behind either.

But, yeah, malaise exists. I had it when I was in high school: “Why do I even need to learn this?” And it’s true that a lot of these questions are short-sighted. Meaning that what students don’t realize is that seemingly impractical work will hone focus and depth of thinking.

But what ChatGPT should make us think about is our understanding of when education is working.

If you get through all the barriers to a successful career and life by using ChatGPT, what does that say about our society?

Here. Let’s let the robot finish this piece with a good summation of what students should get out ELA in high school:

The purpose of learning English Language Arts (ELA) in high school is to develop students’ skills in reading, writing, speaking, and listening. These skills are essential for success in both academic and professional settings, and they can also help students to become more informed and engaged members of their communities. By studying ELA, students learn to express themselves clearly and effectively, to interpret and analyze complex texts, and to think critically and creatively. Additionally, learning ELA can help students to understand and appreciate different perspectives, cultures, and experiences, and can foster empathy, curiosity, and lifelong learning.

Skills, not product. Even ChatGPT knows that.

It’s cute to include the robot, but like anything on the internet, do you really want to be that sure about it’s authority? Or would it be better to slow your roll and contemplate it?

Perhaps it might be good to write that thought out. See what happens.

1 thought on “Another English Teacher Gives Their Opinion on ChatGPT and By Doing So Answers This Question: Will Artificial Intelligence Make Writing as Easy as Using a Stapler?”

Comments are closed.