Virtual Tools, Real Classroom

When you are stressed, practicality is a religion.

At the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year, after we went totally virtual when the pandemic hit in March 2020, I was a bit unsettled.

We were all starting to live with the virus. Still, the memory of full-on pandemic anxiety–memories like studiously watching a YouTube video of a kindly but exhausted healthcare worker walkthrough how to sanitize one’s groceries–seemed too recent to overturn such a reality. Back then, we had no idea that cleaning desks and door knobs and everything else was “hygiene theater,” not productive toward limiting the spread of COVID-19.

Books were not allowed to be checked out of the school library. In our classrooms, we enacted various book quarantine systems, sequestering books for three days before sending them back into circulation.

Students were seated at least three feet apart (our school guidance mandate), and I heavily used digital resources.

Practicality, for many good reasons, was our benchmark to get through the year.

The year went by. It was fine. Far better than virtual learning, but stress crept in through other means.

I started wondering if maybe students only needed their computers to work in the classroom. I had wondered this when I was younger, always wishing I could type instead of write the answers to the worksheets I was given. Back then, computers were far too expensive to entrust to teenagers. Now, there seemed to be a larger contingent of students who despised the inconvenience of writing things in longhand. Plus, wouldn’t it save resources to not print and copy things out all the time.

This was pandemic-thinking. We all were doing stuff like this in various ways, trying to make things a bit easier, a bit more comfortable.

Pre-Pandemic, I had already made it a part of my classroom to have students plot out their own system on how they would “actively read” books. I called this an “Active Reading System.” The system’s design was up to the students. Would they annotate in a paper book they purchased? Would they buy a digital version and use the highlighting and text commenting features? Would they not write in their books at all and just keep a journal of notes?

The Active Reading System had been the focus of my grad school thesis. I have always been interested in the way we dissect books or how we process information, art, and story. It’s fascinating what time, perspective, and experience can garner a text.

That’s all I have wanted for my students, the ability to push one’s self to take a chance on slowing down one’s thinking in a text. To gaze like you would at something you are potentially investing a great deal in, like a new friend or a new home. If we find our own system, one that welcomes us to embrace deepness, we have so much potential.

But all the prescriptive ways that I had tried–like directing students, pen in hand, to annotate a print book for certain themes–haven’t worked for all. And, really, when I annotate myself, my mind lingers on what’s interesting or what is potentially interesting. My curiosity is the system that drives my reading. To make one’s own system, one must remove the barriers so that curiosity is the driving force.

So, I gave students more freedom to think, introducing what I called an “Active Thinking System.” In plain terms, an Active Thinking System was a way students could take notes or plan or do whatever needed to be done to deepen thought, engage with the class, or prepare for a project or piece of writing.

I gave them a bunch of different ways that they could do this, much like my Active Reading System idea: use a notebook, use a hybrid of paper and smartphone camera, use an app, or use a Google Drive.

Instead of the traditional notebook, a thing that previous students were required to use, most students chose to use their computers as their Active Thinking System. And why wouldn’t they?

This choice should have heightened what was happening. Students were choosing computers because they themselves were drawn to the allure of convenience and efficiency.

And so this was my system when we started this year. For anything that I thought needed no computers, I used printer paper, sticky notes, or notecards. There would be tangibility if needed, just not at the forefront.

A Classroom of Screens

And so my classroom turned into a classroom of glowing screens. I cannot really recall a time when laptops were not on desks. I used them for everything.

When we read a story, I shared a Google Doc. When I gave an assignment, it was on our Learning Management System. When I did literally anything in my class, there was a digital system waiting for my students.

It was then that the idealism started leaving.

The worse part of this whole thing is that I am weirdly drawn to books about process and thinking, and I have heavily imbibed so many reasons why thinkers need to plod rather than speed through things. But the beginning of the year was also the time of a new internet fad: the Personal Knowledge Management System.

Personal Knowledge Management Systems are all about creating efficiency in idea acquisition and writing. It is too much to get into here, but know that it is like so many diets: well intentioned philosophies that become more important than reality itself. Once a technology or lifestyle becomes more than the actual other parts of living–it becomes worship, really–you gotta know that something is wrong.

Even as I myself learned best through going slow when reading texts, taking care to plot things out in a large notebook on my desk, I was allowing my students to cater to their own efficiency habits. Of course, I encouraged them at various points to reflect on how well it was going (and some did change their ways for the right reasons), but we often forget how good we are at deluding ourselves, especially in our teenage years when we think like adults but our pre-frontal cortexes are not yet fully developed.

The problem with Personal Knowledge Mangement Systems and computers as note-taking devices in general is that using them feeds on the established delusion that the reason we take notes is for posterity, to study for a test or for some as yet need. Writing itself holds this in its origins. Without writing, we would no longer know the thoughts of Plato or David Hume. Oral history, with all its telephone game errors, wouldn’t have brought us too far.

The main reason we take notes is to be in the moment. To activate our brains by incorporating our hands into the mix. Our ability as an animal species is to think and use tools. At times we proudly view thinking as above and beyond hand-eye-coordination tasks, but the body and the mind are linked–the more we give ourselves to something, the more the brain attends to it.

Usually, when one thinks about that now famous 2014 experiment about note-taking, the Mueller and Oppenheimer experiment at Princeton and UCLA, we think of the superiority of longhand note-taking versus typing note-taking to prepare for a test. But we often overlook the thing that matters most: that, in the study, laptop note-takers transcribed notes for later consultation. They were not letting their minds be drawn into the moment. It was the longhand group that needed to be listening, thinking, and synthesizing information into their own individual language in order to preserve an account of the lecture. The by-product of such actions was a record to study.

As much as we would not like companies to have the last word, a famous notebook company, Field Notes, has the key right in their motto: “I’m not writing it down to remember later, I’m writing it down to remember it now.”

A Mid-Year Transition

Somewhere in November, I looked around the classroom during an activity that required individual active thinking and realized for the whatever-ith time that many students–despite my recommendation to push one’s self to get lost in thought and to let a timer I had set interrupt their thinking–were “done” well before the given time.

Some were playing games or reading books and others were doing other homework. There were constantly battling the constant allure of things a click or tap away. There were other classes to work for and the screen is a dive into whatever you want it to be. It is infinity, along with its supply of dopamine.

I could not pretend anymore that freely using screens–two of them now, a smartphone and a computer–was conducive to good learning.

I’ve struggled with this. Because in a lot of other things in life, I feel like protecting students from life is not allowing them to build resilience. For instance, there are a great many studies going around about how children’s outside play time is going to pot. That it really affects the growing of our resilience to be able to confront problems on our own, to feel failure as an individual, not to be totally hovered over for protection.

In ELA classes, the argument to let students encounter the world on their own is a serious one. Books sometimes have difficult subjects and difficult words. A high school class should be one of the safest places to encounter ideas. Good literature mirrors life, and to think about it is something our society has tasked English teachers to do.

And so I lived in a sort of observational state through December, pondering what to do that would be accepted by my students. I had given them so much freedom, would they be upset when I took it away?

I had given them permission to make their own note-taking systems. Some of them had switched from digital to analog. Some had switched from analog to digital. Some stayed the way they were.

You’d be surprised how much your students follow you. In this age of personalized learning and ensuring students really buy into their learning, you forget how much they need some kind of structure that is provided for them to go further than they thought possible.

It’s the old story of education that we swing one way for good reasons, then go too far, then have to swing the other way for good reasons, then go too far, etc.

I had taken a road from pandemic stay-at-home learning to in-person learning with stay-at-home tools. I had somehow ignored a huge swatch of the bookshelves behind my teacher desk, full of revered educators promoting, in the strongest terms, the power of notebooks and analog focus.

Efficiency just won over.

Semester of Slow

I went to college on the cusp of the age of more affordable laptops. Before cheaper laptops flooded colleges, those who did have them, you’d think, “Man, their parents must be rich.”

But then, you’d be in a lecture hall with that noticeable slant downward, and you’d be in sight of the professor but also so many laptop screens. Not all of them honed in on the lecture.

It wasn’t that I’d fantasized about having a laptop to be present-but-not-present. I wanted to do well in class. But I found myself thinking, “Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to just dip out for a small second to check on something?” Back then, multitasking was still a very holy word.

When I finally put the moola down for a laptop, I usually left it in my bag during class. I was a technology coward. I thought I would look too nerdy and privileged if I used it. And tapping keys is far louder than writing in pen.

That’s changed quite a bit.

In my class, even libraries function in the digital spheres. A lot of my students will read books on their smartphones and even their laptops, especially so in the pandemic era.

For a brief period of time, it was funny to make fun of teenagers and their phones. But, really, it’s all of us. We are all on our phones.

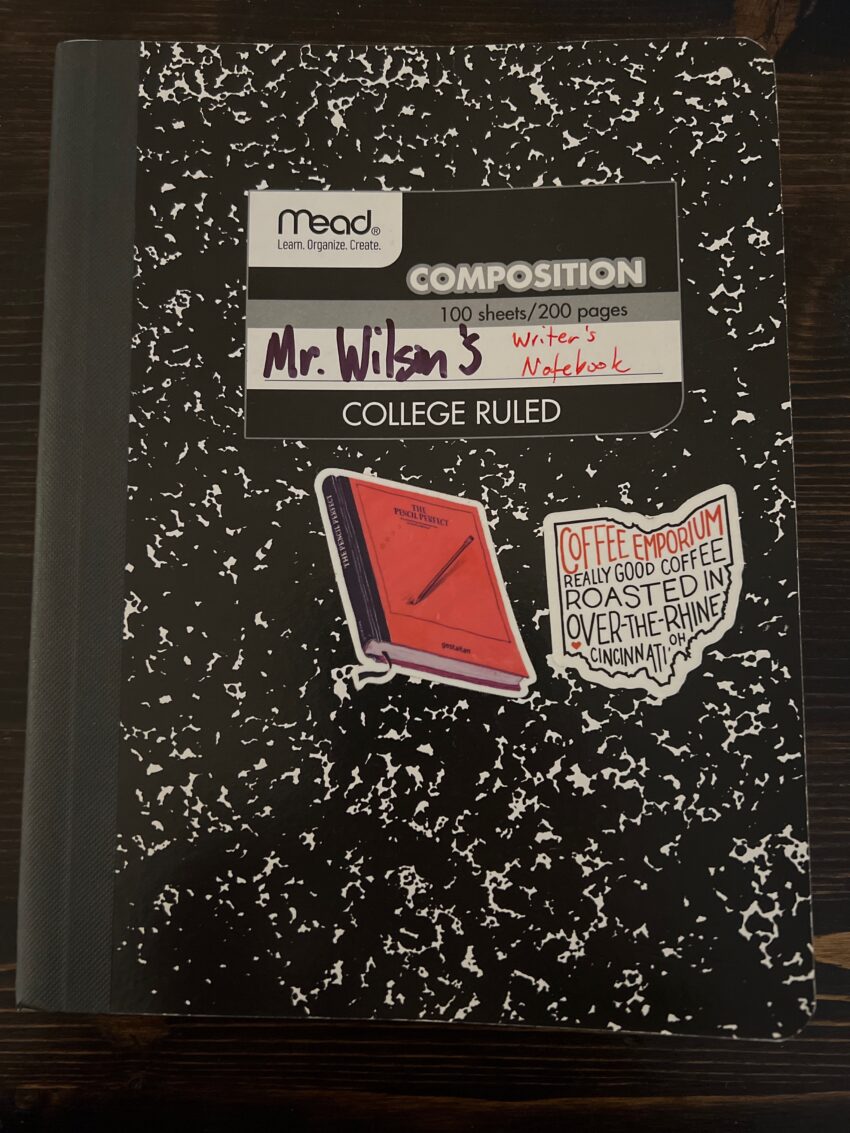

Before the break, students were to get a cheap composition notebook. When we got back this January, I handed out a bunch of Sharpies. Their first entry into their notebook, on the very first page, was to draw a badly drawn self-portrait in under a minute. I wanted them to see this notebook as a messy place for the mind. I wanted them to see a page wasted with something that might have surprised them or caused them to chuckle.

To go along with the notebook, each week I present a five minute pitch for a method of slowness that we don’t really celebrate. Topics range from the element of slowness in slow cookers, leftovers, home-cooked meals (instead of fast food), American auto safety, woodworking, land management, late blooming humans, art appreciation, and Charles Darwin’s working methods.

We only use the computers when we write.

We cannot deny how humans have done well to master the arts of efficiency. Without efficiency as our ideal, we would have never created computers. But we are not computers ourselves. We are built by a very slow process, evolution, and still retain the so many mechanics that require a slow pace.

If one could rebuild humans, to be entirely efficient, perhaps we wouldn’t sleep. But to do that, we would compromise the very trade off that helped build our brains to what they are.

Much like our technology has two sides (fire gives warmth and destroys; social media connects and disconnects), the speed we do things also has two sides. Just because many of the faster ways are easier to see in terms of success in our economy and in the impressiveness of social spheres, it is no substitute for the slow arc of good things.

We need both, and it seems that more and more we need to be reminded of that line that my students just read during 1st semester, a line from Romeo and Juliet, delivered by the well-meaning Friar Laurence: “Wisely and slow, they stumble that run fast.”